Dickens and family are still en route to Marseilles to catch that boat to Genoa, having left Paris on 7th July. He writes of this ensuing stage that ‘a sketch of one day’s proceeding is a sketch of all three’, referring to the monotony and uniformity of modern travel (a phenomena which James Buzard explores thoroughly in The Beaten Track). With transport becoming ever faster and more efficient, travel becomes defined more by destinations than by the route itself, which is reduced to a mere blur out the window.

There is little more than one variety in the appearance of the country, for the first two days. From a dreary plain, to an interminable avenue, and from an interminable avenue to a dreary plain again.

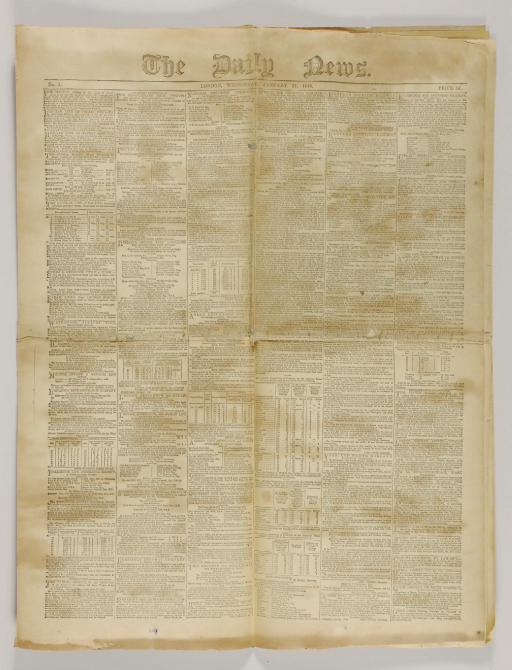

Harsh. But there’s an inherent contradiction in Dickens’ dismissive reduction of three days’ travel all being alike, which is that this quote comes not from his personal correspondence but from Pictures from Italy, and moreover, it’s original, unfinished iteration, Travelling Letters which appeared in the Daily News in the early part of 1846. What’s really strange is that Dickens started his series of Travelling Letters with the departure from Paris. So here we have what is apparently a fairly routine, repetitive, boring part of the journey…and Dickens selects that as his opening. Paris itself barely gets a mention, and we have a while longer yet to wait before Dickens gets to Italy. One might very reasonably ask then, why does Dickens start here?

Part of the answer can be found in precedent. The handbooks pioneered by Murray and Baedeker included details of the journey as much as the location, so that the guide to Northern Italy would provide information on the passage through France. Equally, previous travel literature from other writers (e.g. Smollett, Goethe, Addison, Thackeray) also described the journey there as much as the final destination. Travel abroad is not defined by national borders so much as the exoticism simply of being outside England, even at a time when increased travel (and travel literature) was making the continent increasingly familiar. Starting from Paris allows Dickens to dive straight in to the action of travel abroad, eschewing the familiar by not beginning from his home in London, and attempting to recreate that sense of excitement, novelty and innovation of early travellers. The problem with this theory is that journey which Dickens describes here in this opening section is, well, a little dull.

But it should also be noted that Dickens’ first ‘Travelling Letter’ and the corresponding chapter in Pictures ‘Going Through France’, closes with a delightful, and typically Dickensian, account of staying in a French hotel. Here the sleepy monotony of the road is swapped for action and noise – literally in the case of the carriage which bursts into noise over the uneven pavements:

As if the equipage were a great firework, and the mere sight of a smoking cottage chimney had lighted it, instantly it begins to crack and splutter, as if the very devil were in it. Crack, crack, crack, crack. Crack-crack-crack. Crick-crack. Crick-crack. Helo! Hola! Vite! Voleur! Briagnd! Hi hi hi! En r-r-r-r-r-route! Whip, wheels, driver, stones, beggars, children, crack, crack crack; helo! hola! charite pour l’amour de Dieu! crick-crack-crick-crack; crick, crick, crick; bump, jolt, crack, bump, crick-crack; round the corner, up the narrow street, down the paved hill on the other side; in the gutter; bump, bump; jolt, jog, crick, crick, crick; crack, crack, crack;

It’s an extraordinary showcase of onomatopoeia as the sleepiness of the countryside journey explodes into the excitement of arrival, the bustle of the hosts, the novelty of a new location to explore. Could it be tthen hat Dickens deliberately opens with the apparent monotony of the long journey deliberately to establish in the reader’s experience the same excitement that the travellers themselves feel upon arrival at a destination? The writing certainly comes alive as the description changes from dreary landscapes to fawning staff and inevitable bickering over the bill between the hotel owner and ‘The Brave Courier’ Louis Roche – but more on him, and Dickens’ other travelling companions, in the next post.

Leave a comment